BIOGRAPHY

American, 1913-2001

Mercedes Matter was destined for a life in art. She was the daughter of Mercedes de Cordoba, a former model for Edward Steichen and other members of the Photo-Secession, and Arthur B. Carles, an important early modernist American painter who studied the art of Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse in Paris in the 1910s. This early and persistent exposure to modern art led Matter herself to begin painting at the age of six.

In the early 1930s, she studied with the artist Hans Hofmann, like nearly every important American abstract painter of the next generation. This German-born painter is of course famous for teaching the concepts of abstract painting that would define the New York School: the “push-pull” approach to composition and the focus on the picture plane.

During the Depression, Matter worked for the Works Progress Administration alongside Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, and Lee Krasner. The project she and de Kooning collaborated on was directed by Fernand Léger, for whom she served as a translator.

In the early 1950s, Mercedes was among the first female members of the Club, an organization of downtown artists that held frequent discussion evenings; she was also a regular at the Cedar Tavern. For Mercedes, “The Club was marvelous. It brought together in one place, at one time, the greatest diversity of artists—as nothing had done before or has since. . . . The end of that marvelous time came when American art became big business.”

Matter was a noted educator and would go on to become one of the founders of the New York Studio School. Beginning in 1953, Matter taught at the Philadelphia College of Art (now University of the Arts), Pratt Institute and New York University. Based on her teaching experiences she wrote an article for Art News in 1963 titled ”What’s Wrong with U.S. Art Schools?” In it, she lamented the phasing out of the extended studio classes required to initiate ”that painfully slow education of the senses,” which she considered an artist’s life work.

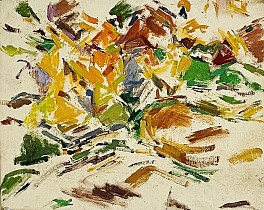

Matter practiced as she preached, spending months, and sometimes years, working on drawings and paintings that usually began as still life’s and evolved into near-abstractions animated by thatched lines that attested to her devotion to the work of Giacometti and Cézanne. She was known for her easel-size paintings (and charcoal on canvas drawings) based on the still life and the figure, but abstracted into a force field of compressed space with an agitated line. Her work was about capturing the electric energy between objects. Source imagery was rendered nearly unrecognizable. It was a painterly language and drawing style entirely her own.

Matter either lacked the confidence or was too uncompromising to pursue exhibiting her work very much in her own lifetime. An example: Leo Castelli offered her a solo exhibition in the 1950s, and she declined, telling him she wasn’t ready. Still, Matter was at the very center of the art world. Her life — and her position as an educator, friend, lover, or mentor to some of the most influential artists and art critics of the time — reads like a history of the most vanguard 20th-century art movements.

Her work is included in the collection of the Whitney, among other museums.